Bangladesh at a Political Inflection Point: Transition, Interim Governance, and Leadership Uncertainty

How institutional fragility, political polarization, and economic pressure are shaping Bangladesh’s post-transition trajectory.

Bangladesh is entering a highly sensitive political phase defined by institutional strain, public distrust, and leadership uncertainty. Political transitions in the country are rarely administrative exercises; they are high-stakes power recalibrations that test the durability of state structures. The recent interim governance period must be understood within this context. Interim administrations in Bangladesh historically operate under compressed timelines and immense scrutiny. Their primary mandate is not transformation but stabilization—ensuring continuity of governance, managing electoral logistics, preventing unrest, and sustaining economic confidence during political uncertainty.

The interim government’s operational difficulty lies in perceived neutrality. In deeply polarized political systems, even procedural reforms can be interpreted as strategic maneuvers. Administrative reshuffles, law enforcement positioning, and electoral oversight decisions are rarely viewed as technical adjustments. They are seen as signals of political alignment. Under such conditions, maintaining institutional credibility becomes as important as maintaining public order. If the interim administration focused heavily on electoral process integrity and macroeconomic stabilization, it would have been operating within narrow fiscal and political margins.

The possible emergence of Tarique Rahman as prime minister represents a structural shift rather than merely a leadership change. His political capital is rooted in established party networks and long-standing opposition identity. A government led by him would likely prioritize consolidation of party influence within state institutions and recalibration of policy directions. The opportunity in such a transition lies in political clarity—voters and institutions would know the direction of authority. However, risks would include bureaucratic friction, opposition mobilization, and the challenge of converting political momentum into administrative performance.

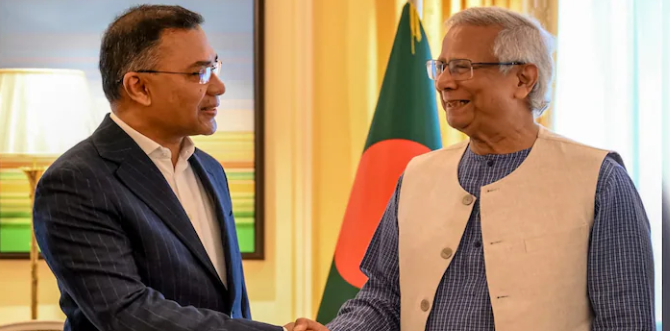

The discourse surrounding Muhammad Yunus introduces a different dimension to the political debate. Yunus represents technocratic reformism and global recognition rather than traditional party power. However, reformist credibility in economic or social entrepreneurship does not automatically translate into state governance effectiveness. Governing a nation requires coalition management, parliamentary negotiation, security oversight, and fiscal control—skills distinct from policy innovation or social finance leadership. Criticism directed at reform-oriented leadership often reflects the tension between expectation and institutional capacity rather than deliberate systemic damage.

Bangladesh’s structural challenges persist regardless of leadership configuration. Inflation, foreign reserve pressures, youth employment demand, and export sector dependency—particularly in garments—continue to define economic vulnerability. Political transition does not alter macroeconomic fundamentals overnight. Any prime minister, whether party-based or reformist, must operate within these constraints. Failure to manage economic optics can quickly erode political legitimacy.

Another critical variable is institutional trust. Prolonged polarization weakens confidence in electoral bodies, judiciary independence, and administrative neutrality. When transitions are interpreted as existential battles rather than democratic cycles, institutions suffer long-term credibility damage. The real threat to Bangladesh is not individual leadership but systemic erosion of institutional trust.

Geopolitically, Bangladesh occupies a strategic corridor between India and the Indo-Pacific power competition environment. Leadership shifts influence trade negotiations, infrastructure alignment, and diplomatic signaling. A stable administration can leverage geography for economic advantage. A volatile administration risks external pressure and investment hesitation.

Ultimately, Bangladesh stands at a strategic inflection point. If political transition results in legitimacy, institutional discipline, and macroeconomic focus, the system stabilizes and strengthens. If it results in retaliatory governance, bureaucratic purges, and escalating confrontation, volatility deepens. Nations are rarely destroyed by one leader alone; they are weakened by prolonged institutional fragility and unresolved polarization.

Bangladesh’s future will depend less on rhetoric and more on governance execution. Stability will emerge not from personality dominance but from institutional resilience and economic discipline.